Sometimes, you meet the most incredible people, who challenge themselves as athletes with diabetes. In this article, we will meet three mountain climbers and athletes with Type 1 Diabetes who have made summit on Mt. Everest. They represent the countries of Spain, Canada, and the United States.

Mt Everest is dangerous for anyone

What’s so incredible about these three men, is that they have beat several sets of odds by making it not only to the summit of Mt. Everest, but down again. The fact is, more people die on the way down from Mt. Everest, after they have completed their dream of reaching the summit.

Since alpiners began climbing Everest back in 1921, there have been 290 people who have died. It’s estimated that of those, over 120 dead bodies still lie in rest on the mountain.

Let’s learn about our three Type 1 climbers:

In the order of ascent, we will interview Josu Fiejoo from Spain, who you may remember from the recent article here on astronauts, and Will Cross from the USA, Sebastien Sasseville from Canada. Let’s see how these incredible athletes with diabetes conquered the highest mountain in the world, a mountain that has taken the lives of many healthy hikers with no chronic condition whatsoever.

Ascent to Mt. Everest:

- Josu Feijoo, Spain - summited May 18, 2006

- Will Cross, USA – summited May 26, 2006

- Sebastien Sasseville, Canada – summited May 25, 2008

Their stories are inspiring to others, no matter what their goals. The moral is, even when climbing the highest mountain, you should not let diabetes stand in your way. Most of you will not attempt to climb Mt. Everest, but these stories show us that it can be done. Impossible is no longer a phrase we use when referring to diabetes. If you can dream it, you can achieve it.

Josu Fiejoo – the first person with Type 1 Diabetes to Summit Mt. Everest

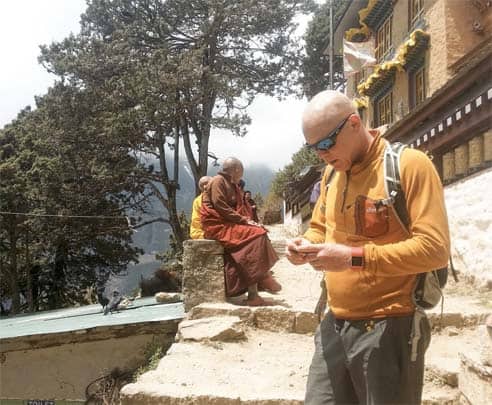

We first met Josu Fiejoo interviewing for our recent astronaut article. He’s quite an amazing athlete, and moutain climber. Josu is from Spain, and he was the first Type 1 Diabetic to summit Mt. Everest. In the photo above, Josu held up his glucometer, while wearing his oxygen mask at 7,950 meters above sea level.

Interview with Josu Fiejoo, Spain

Fiejoo is also a professional coach. He recently spoke at a conference in Melbourne, Australia, for the International Diabetes Federation (IDF). He speaks on the medical applications of his research related to diabetes in space, and for the improvement of diabetes overall. He spoke before 192 delegates from all over the world.

You may visit Josu’s website at: www.josufeijoo.com

Josu: “I made a summit on Everest on May 18, 2006, on the north side (the difficult one). I got oxygen from 8,000 meters. I was accompanied by my Sherpa Mukhu Sherpa (who has climbed it 7 times). By then I had already climbed the central Shisha Pagma of 8,012 meters high, the Aconcagua, the Mckinley, 4 times the Nont-Blanc, 1 time the Materhon (Matterhorn), and the Eiger. I was a professional mountaineer. I had tried the Cho-Oyu of 8201 meters, climbed to 8,000 meters without oxygen, the Broad Peak from 8,047 to 7,800 meters, and the Anapurna I from 8,091 meters to 6500 meters, but there were too many avalanches and I left it.

I have tried Everest on 6 occasions: 1993; 1998: 2000: 2003; 2004; 2006. The sixth was the good one. The other times, I always reached 8000 meters without oxygen, and from there it did not happen. Then in 2006, I decided to go with oxygen the last day and triumphed - alpinistically, technically always without problems, and diabetes was not an impediment. I had the same behavior as in my city.

On the mountain, I do exactly like when I'm in my city, in my normal life. What I do, along with the recommendations of my endocrine physician, is to anticipate what may happen to me in the high mountains. I have climbed mountains every weekend for 25 years, and I know myself very well. So, I simulated in the mountains near my city to get ready.

I do not use an insulin pump, but I imagine it will work without problems. We go with clothes that support up to 50 degrees centigrade below zero, so without problems.

I believe that well protected, blood glucose meter, pump, and insulin pens, work perfectly. Look at the photo I sent. I am injecting insulin, and doing a glucose control at 8,350 meters in the field 3 at 40 degrees below zero.

I always carry several pens of insulin, both fast and slow, stuck to my body, inside the feathered diver that protects me from the cold outside. Also, my Sherpa takes identical pens to carry with me for reserve.

Normally, you go up Everest in about 45 days. It costs me 32 days, since I arrived at the base camp on April 17, until I reached the top on May 18 at 08:15. At the top of the hill was my Sherpa Mukthu and Francisco Javier Martin Sanz with his Sherpas Pasang.

I did not have any problem derived from my diabetes, and in the mountains, I found what one usually finds at that altitude. Nothing happened worth mentioning. For me, it was an escalation, a lot of concentration, and responsibility. I was the expedition leader of three other Spanish companions (who also made top) and their Sherpas. So my diabetes could not be an excuse.

I was diagnosed with diabetes on December 28, 1989. By then, I was already a mountain climber. I do not remember any serious episode in my life until that moment.

If after injecting insulin, I have suffered hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia, that’s the usual - like any other diabetic. Due to my professionalism as a climber, and conqueror of the two geographical poles (North and South), I try to anticipate the pathologies of the disease. I walked the North and South Geographical Poles, without any help, in 40 degrees below zero, but as I said, diabetes cannot be an excuse.”

Thank, Josu, for sharing your story with The Diabetes Council.

Interview with Will Cross, USA – the second person with T1D to summit Everest

Will Cross from the USA was the second person in history with T1D to summit Mt. Everest. He made summit shortly after Josu, in May of 2006. Will resides in Pittsburg, and is a motivational speaker and is a spokesperson for Tandem Diabetes Care.

“I speak about diabetes, and what it’s like to do large expeditions with Type 1. Because I’m representing a diabetes company, I’m talking about how I use my pump when I climb. I was just in Nepal for a month climbing, and I wore a Tandem on one side, a Dexcom CGM on the other. I’m always plugged in, so that’s what I talk about.

You may visit Will’s website here: http://www.willcrossmotivates.com/

When I climbed Everest, I didn’t have the insulin pump and the CGM at that time. They weren’t as reliable as they are now. I used insulin pens, because the insulin in a pen is more stable than in a bottle, so it gives me greater protection with temperature variance.

I took a few with me just in case. The variability of a glucometer is high anyway, so I heated it up, and kept it warm throughout the day, the best that I could inside my pack. I combined that with urine tests during the day, because I can’t always stop and take a blood test when I would like to.

The main challenge was when you go up, when you do a big mountain, you spend time working really hard for about five days. Then you’re lazy sitting around for about five days at base camp. Everything that you know the school kid and parent goes through, when you have one schedule for school, and then as soon as you get that figured out, you get the weekend, and it all goes haywire. Then Sunday comes again, and it all settles down. Then the new week starts. And the same thing happens with climbing. Those rest days are really the most difficult.

I’m was in base camp for two months, and it’s the months of April and May. I went then, because that’s when the weather is best.

I am not going to Summit Mt. Everest again. I go to the Himalayas every year for the last 15 years. I’m doing lower peaks now, and I’m focused on a trip next year to cross Greenland, and Sebastien will be a part of that. I wouldn’t go to climb Mt. Everest now. I’ll tell you that much. It’s a dangerous place, and it’s easily twice as crowded now, as when I went. It’s a very volatile environment. Seven to ten people are going to die every season, and people are always shocked at that, but you’re just not designed to be above 8,000 meters.

I had lows and highs, and both were extreme in a few different cases. And sometimes that happens with the best of management. Insulin pumps and CGMs weren’t around then, so I just didn’t have that immediate feedback, or data like we have now. I will have both in Greenland. I can get it all right there.

I don’t have to stop and do anything different once the CGM is in. I can consistently read my sugar, and I can do it right on the pump; and ten years ago, we couldn’t do that. The t-slim X2, and all Tandem pumps have been tested at altitudes up to 10,000 feet at standard operating temperatures.

It also really helps me in the field field because the Tandem pump is not battery operated, it plugs in just like a phone and then I can use solar power when in the field. Not having a battery also decreases the environmental waste which is important when in the Himalaya, and I can plug it into my solar panel. I never could do that before. I was a little hesitant. I thought, oh my goodness, I can’t just bring a load of batteries, but it’s actually better, to my relief.

I always check my hemoglobin, and my eyes before I go. I want to make sure that I’m not damaging my eyes in particular at the high altitude. If it’s a long trip, I’ll go to the dentist. You know a dental problem can be a real problem, for example, in the middle of Antarctica.

I order more insulin than is typically necessary. I’m going to take twice that I think I need for the trip, in case you get the odd batch of insulin. Sometimes insulin is stolen, or it freezes, like in third world countries, so I just want to be prepared for every eventuality. I always take a lot of food with me, and have extra on a big expedition.

Food logistics on a large trip can always go wrong. I was on a long trip, and the food was lost, and we had to live off the land for three weeks. Now that’s pretty challenging with diabetes. I could deal with it, but I certainly don’t want to repeat it, so I take a lot of gels, protein bars, protein powder, and rehydration drinks.

In terms of blood glucose, I take a couple meters. In terms of pumps, I take a vacation meter. Most companies provide those. They basically loan it to you. I did use it once. Just like any machine, or a phone, if it goes wrong, you want to replace it.

Typically, I’ll take a high-quality thermos, the type that a construction worker would take if he works in the middle of a Canadian oil field. And then, I’ll typically wrap the insulin in tin foil, and mark it with athletic tape, so I’ll know what is what. If it’s really cold, I’ll put it in my sleeping bag. If it’s not so cold, I’ll make sure it’s just inside the tent with me, where it’s going to be a good 10 degrees warmer than outside.

I always split up my insulin, so that I have some, and my partner has some. And you know that way if there is ever a problem, I know that there is always extra insulin somewhere.

Here’s one tip you may not have heard is related to climbing with the pump. Obviously, I have one pump on, but I have two insertion (pump) sets like 2 ports where I plug in. If I am working hard and sweating hard, and one rips out, then instead of breaking out all of my pump supplies, I can just immediately turn over to the other site and insert there. This is a good tip for any sport where you may be isolated. It’s important if you are involved in sports, theatre, music, or something where you don’t want to leave the performance (or event). You’ve got to take care of yourself.

When you get up to the top of Everest, you don’t even think about your diabetes.”

Will is married, with four healthy children, two boys, and two girls. Two are in high school, and two are in college. One is in nursing school in Washington State. I’ve got one at West Point, and then the other two in high school, in seventh and ninth grade. . Max is in 9th grade, and Chloe is in 7th grade. None of Will’s children have T1D so far.

“So far, so good,” he said. “We’ve been very lucky.”

Interview with Sebastien Sasseville, Canada – the third person with T1D to summit Everest

Sebastien Sasseville’s does motivational talks for corporations and for people with diabetes.

Sebastien Sasseville, a runner, alpiner, and athlete from Canada, was the third person in history to make summit on Everest with T1D in May 25, 2008. He was the first T1D to make summit from Canada. He is a full-time corporate leadership and change management motivational speaker, and he occasionally does inspirational and technical talks for people with diabetes, and professional athletes with diabetes.

You may visit his website here: http://sebinspire.com/en/

Also, view his recent inspirational Ted Talk, “Why I am glad I was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes”.

Sebastien: “To climb Everest, patience is definitely one thing, and I know it’s not the kind of tip that says, ‘do this and it works,’ that sometimes people are looking for, but that’s definitely a part of the equation.

The second thing, I took a lot of notes. This whole dream, it just started with you need to climb, you need to go out camping, you need to do some trekking, so it starts slowly, with very humble beginnings. If you can’t go for a six hour walk in the forest just hiking without being able to control your blood sugars, then there’s no way you’re going to be able to climb Everest. So, humble beginnings are another part of it.

You figure out what works for you in terms of glucose and insulin intake, and finding the balance between the two. That’s important, because you need to avoid hypoglycemia at all costs when you’re up there, but you also, and this is where it gets complicated, you also need to fuel your body. So, to cut down on food an insulin too much to avoid lows - that’s going to work, you will avoid lows, but you will not have the energy you need to climb all day for several months.

Learning how to take carbs and insulin while exercising, and maintaining good blood glucose is important, because when I say avoid hypos at all cost, that doesn’t mean you should keep your blood sugars up in the 200s, and you are fine. There’s no way you will be able to perform if your blood sugar is that high.

When your blood glucose monitor is in your outer, front pocket on your jacket, you figure out that you will test more than if your blood glucose monitor is in your backpack. When it’s in your backpack, you have to stop, and take your backpack off. That sounds very benign, but little things like that - your monitor needs to be very close, and that will make you test more. If you test more, you will spot trends; and if you spot trends, then you will catch your blood sugar rising or falling sooner. If you find out sooner, then you can prevent high or low blood sugars. This allows you to perform better.

I was on an Animas pump when I climbed Mt Everest. I’m still on the pump which to me is the best pump, so it makes it even more heartbreaking that they are going to withdraw from that business, but it is what it is.

I wear a CGM 24/7 now, but it’s one of those things that I would have liked to have ten years ago when I climbed Mt. Everest.

It’s about a two months process. You are not hiking every single day, so there’s a lot of time spent in camps where you just wait, and you are acclimating to altitude. That’s when your body learns to produce more red blood cells. Just to get to base camp is about ten days walk, and then you’re going to sit at base camp for several days, and go through your gear, and make sure everything works.

Then the climbing process starts, and it’s not a straight line from the bottom to the top, so you go up and down, and up and down, many times. And that’s the only way your body can adapt to higher altitudes. For example, you climb to camp one, and you stay there. Then you climb back down to base camp. That process takes about a month up to camp 3, then to come back down again.

Going down, it’s tough mentally and physically. You know you worked so hard to get to Camp 2; long days, tough days, dangerous days. You accomplish that, and two days later come down back to base camp, and you must start all over again.

That’s the process. You must love the process if you want to get to the summit. You must forget the summit, if you know what I mean.

It’s the same thing with diabetes, you must forget that perfect A1C you’re trying to reach, and learn to love the process. Learn to love yourself, and trying to take care of your body. Take care of diabetes, and if you do that, the outcome is going to be good control.

You are in base camp for ten days. If you’re ready, say after a month, then you will start looking at weather reports closely, and you’ll start planning your summit. When you’re ready, to get to the summit from base camp; that’s about 3-4 days, then back down, so maybe a week in total. That’s an exciting part of the climb. Obviously because sometimes it’s hard to stay focused during the first month, but now you can see the summit, and you’re leaving base camp and you’re going to the top.

You could be stuck in bad weather, so sudden weather change can be very dangerous out there. You could run into avalanches, or experience altitude sickness.

The most dangerous thing up there is your ego one-hundred percent.

If you wait for things to go wrong to turn around, it’s too late. And that’s what makes Everest so fascinating. So, basically you must be able to listen to your instinct, and turn around before something goes wrong. But very few people can do that, because it’s Mt. Everest, and people get obsessed with the summit, and you want to get up there, so why would you turn around when things are still fine?

That explains why most people who die on Mt. Everest, die on the way down. They summitted, but they don’t ever make it back home. That’s people not understanding that the summit is the half mark, it’s not the finish line. So, you must plan your energy levels, your oxygen levels; everything - your motivation, your passion, everything you’ve got, so that you can make it back down to base camp. It’s a long way down from the summit.

For low blood sugars, I took a lot of glucose gels with me, a basically because they don’t freeze. They were always kept close to my body, so that they were not too cold. The gels, that was my strategy, and lots of them. I always planned for strategy for the worse, and then worse than worse. I think that’s important up there.

We had a team of Sherpa with us. We had a guy with Crohn’s Disease, we had a guy with Type 1 (that was me), we had an amputee who was 71 years old, so we had a special team. I’m the only one who made it that year. The guy with Crohn’s, and another guy, went back. Another guy, who was the fifth guy on our team; they both went back two years later, and summitted.

We knew each other before. We had climbed a little bit together in Vancouver, and we had planned a trip together. That was important to us. A lot of people just go to Everest, and meet their team mates there. To me, that is not the way you want to do it.

We all departed together from Camp 4 for the summit bid, and they made it about half way up to the summit. I finished the climb with 2 Sherpas, and two of our expedition leaders.

I didn’t have anyone on my team carry extra supplies for me. That was my responsibility. And yes, they have them trained on what to do, and what not to do in an emergency. But at the end of the day, it was my thing, and there was very, very little they could have done.

Nothing dramatic related to diabetes happened on Everest. I had a few highs and a few lows, which every person with diabetes goes through that. I forgot insulin in the tent for one night, and it froze. I had tons of back-up. It was frustrating, because even though I had tons of insulin, the thought in my mind was that I made a mistake that could have been costly; and those things are fine, I’m ok with that.

I’m not a control freak that wants everything to be perfect, but it was an important mistake, and it was just a distraction, so that’s what stays with you – even though you’ve got tons of back-ups, but it keeps you honest.

So, sometimes you’ve got to welcome it, and understand it’s something that drives you to be better the next day.

A challenge with insulin is that it’s good at room temperature for 30 days, but when you climb Everest, you are gone for two months. You’ll have part of your supplies that need to be refrigerated. There’s no power at these camps obviously, so there’s no fridge. I have thermos, so with a thermal heater, and thermos, I would look at insulin temperature every hour. Do I need to put it in the sun? Do I need to put it on some ice?

It was not stressful, but it was very labor intensive, just to make sure that for the first four weeks, my insulin was cool. And that was only four weeks, because once you achieve refrigeration for four weeks, even though you’re only halfway through the climb, you don’t have to worry. To get to that half mark, with insulin that has not been refrigerated, that was a big victory. It’s all those little things that complicate it, and complicate your life on Everest, as a Type 1 Diabetic.

There are two things about the blood glucose monitor. If it’s too cold, they won’t work. The most important thing, they’re not proved to go up above 10,000 feet. Base camp is at 10,000 feet. That’s where you start. So, you’re not supposed to use them up there, so they’ll still give you a number, but the higher you go in altitude, the less accurate this number becomes.

But you need the number. You need the reading. That’s probably the biggest challenge, management of blood glucose is already a humongous challenge at sea level and life. But imagine being in a situation – a very extreme situation climbing Mt. Everest. On top of that, your measurement instrument does not work, so how do you go around that?

It’s a combination of a lot of things, mostly getting to know your body before you climb Mt. Everest. You must get to a point where you can almost put it on auto-pilot. You know exactly how much insulin you need, when you need it. You know how many grams of carbs to take, and you are still testing. Then understanding the imperfection of the monitor, and that the higher you go, the least you start trusting the number. You can test a few times in a row, get the average amount, then when you’re in your tent at night, surrounded by food, you can be a little bit more aggressive with insulin.

If you go low, it’s not a huge deal, you’ll just eat, and you’ll be fine. Whereas, if you test your blood sugar during the day, and you’re climbing, your moving, you’re active. Then you’re very sensitive to insulin. But if you are not trusting the result of the monitor, then you’ll be a lot more conservative with insulin, and you’ll take a little less, just in case the number was falsely elevated. That happened a lot at high altitude. So, that was big challenge.

Little things, like insulin pumps: I couldn’t wear it at the belt level, so I had a special strap around the shoulders. That way it wouldn’t interfere with my harness. It was always readily accessible, and with the infusion set, everything was contained. It wasn’t between my harness.

It’s not that complicated if you take a moment to think about it. There is just that commitment that you need to be very strong for two months in a row. You need to do everything that you can, so that this thing is controlled. So that you can focus on climbing, and it was a lot of work. That’s for sure, but it was worth it.

I have also raced across Canada, and ran in the Sahara Desert race, and I’ve climbed a lot of mountains. Everest – it’s two months. You commit, focus, work hard, and come home.

When I ran across Canada, it took three months. It was like a marathon a day. All I wanted to do was to have people change how they felt, and how they feel about the disease. If you change that, then everything’s going to change – you will go get the knowledge you need. Everybody can read an article, and everybody can test their blood sugar.

Diabetes is not that hard, but because it’s emotionally difficult, then that’s why we are not as emotionally engaged as we should be sometimes. If you help people with that relation part of it, and accepting diabetes, learning to feel good about it, then that doesn’t mean you love it, right? It just means it’s in your life, you deal with it, and that’s it. And you are willing to learn from it, if you start there, then the rest is just technical stuff. Go climb mount Everest, if you want but be ready for a challenge.

TheDiabetesCouncil Article | Reviewed by Dr. Christine Traxler MD on May 20, 2020