One of my favorite diabetes classes to teach is my migrant farmworker’s class. This class lets me get right in community health grass roots programs where diabetes education can really make a difference. What they lack in resources, they gain in community and family support that is unmistakably helpful and effective, not to mention uplifting.

Contents

Henrico’s story

A large migrant farmworker class, which included children, grandchildren, and community members, was held at the local high school’s health center. Along with a healthy meal, daycare was provided as well as Spanish materials for diabetes management. All class members signed a release for pictures.

Henrico, a farmworker, came in to see the nurse practitioner. He had lost 30 pounds recently. He was cachectic, literally bones with skin pulled over it. He was limping into the clinic in his work boots, favoring his left leg. The lab did a random blood sugar that was 1064 mg/dL. He looked dehydrated, and exhausted.

Melina, one of our farmworker staff, walked him in.

“Me siento muy cansado,” said Henrico.

Melina interpreted, “I feel very tired,” she said.

The worst part was when Henrico took his boots off. Inside his work boots, with dirty socks from working the fields that morning, Enrico had a blister. It looked just like an ordinary looking blister.

The nurse practitioner said, “Oh my, that’s not good.” I couldn’t hide the concern on my face. With a blood sugar of over 1000 mg/dL, Henrico’s blister could be of great concern.

He was admitted to the hospital that day, where he received treatment to stabilize his blood sugars, and start him on insulin. Henrico was discharged with little understanding of his diabetes, and what to do. We had to make home visits for the next several weeks, explaining how to administer his insulin.

He lived in a mobile home, with three other male farmworkers. There were piles of beer cans stacked up outside near the deck as you entered on the small wooden porch. Workmen were fixing the floors, and there was a large hole in the hallway.

In the refrigerator, where Henrico went to pull out his insulin, there was an immediate overflowing of colorful harvest. From squash, to cucumbers, tomatoes, blueberries, they had an abundance of produce for healthy eating.

We discussed alcohol with Henrico, who insisted that his roommates drank beer, but he didn’t. After daily home visits, which included checkups of his foot blister, Henrico’s toe was looking like it was infected.

His blood sugars remained so elevated that it became apparent that he hadn’t been taking his insulin. He later stated to a farmworker that he knew how, but didn’t want to do it.

Henrico ended up with amputation two weeks after being diagnosed with LADA (Latent Autoimmune Diabetes in Adults). Following a rehabilitation stint funded by the farmworker program, he needed a prosthesis.

The farmworker staff set out to raise money for Enrico’s leg. Today, he walks well on his prosthesis. It’s unfortunate that it took so long for Enrico to realize that his diabetes was serious, and to self-manage.

Now, he would not miss a shot of insulin. He made the effort to come to diabetes classes, where he learned more. He now carries his cooler and insulin with him, along with snacks, and his diabetes supplies when he supervises the warehouse. His boss found him a sitting job, and he no longer migrates from farm to farm.

Public health and the migrant farmworker

I began working with the farmworker population 20 years ago, through public health in Marion County, South Carolina. I remember driving down the long stretch of road that led to Centenary, SC, with nothing but directions to turn by the broken-down Hearst in the field.

Working in migrant camps

Down the windy, pot-hole pitted road, to the row of trailers, stretched out through a dirt field, I came across the migrant camp. A farmer had made this into a make-shift mobile home park for his workers.

One double-wide served as the community grocery. There were several workers hanging around outside, as I entered to dress a wound for the woman with diabetes who ran the small community store.

Cultural religious importance in Hispanic culture

Farther down the row, a tent revival structure was adorned with statue of the Virgin Guadalupe, other saints, and white candles lit and strategically placed around the tent. Nearby, chickens clucked and scratched at dirt in the lean-to pen.

I learned quickly that you can’t underestimate the power of prayer when working with the Hispanic community. Not only are there altars in the small Mexican American communities that serve as a place to gather for prayer, there are altars in homes, where families gather.

They can be the focus of the family home. Often, pictures of Jesus, or of the Virgin Mary are on the walls, and candlelit prayer is often believed to heal the sick.

I advise reading the following articles:

Hispanics have a high incidence of Diabetes, and other chronic diseases

Most Hispanics do suffer from some form of chronic health conditions. They have a high rate of heart disease, and they are one and a half times as likely to develop diabetes.

Since 2006, it was estimated that 3 to 5 million have come with green cards to work our farms each year. The estimate has likely increased since then.

The Hispanic farmworker community is poor, and underserved

The Hispanic farmworker community is one of our poorest populations, with little access to care. A combination of low socio-economic status, combined with working conditions that are often questionable, and healthcare access that is limited at best, they are a highly underserved population within the United States. Consequently, their death rate is higher than the US citizens that they serve.

What makes someone a farmworker?

Not all are from Mexico. There are also Puerto Rican, Cuban, and Central and South American cultures represented in farms across America. Still, a full 85% of farmworkers are Hispanic.

Some are indigenous migrants, or non-Latino/Hispanic who travel the eastern parts of the United States, working in agriculture. Documenting the flow of migrant workers across the US is a difficult task, and information is lacking.

It’s hard to pin-point who qualifies as a migrant worker, how many there are and, where they have come from. This presents a clear public health concern, as they may have been exposed to communicable diseases.

Tracking of migrants is poor

Public health efforts to track migrant movement can be further facilitated by effort in farmworker clinics in rural areas. States should then be better able to estimate the number of migrants moving in and out, and to be better prepared to provide public health services. Not only is diabetes of concern, but also, other diseases, including tuberculosis and HIV, which require medical attention and follow-up that the migrant population may not have access to. (1)

The need for Diabetes education in the migrant farmworker population

Migrants are a vulnerable population, as by the name, they are always moving. When one season is over, they move on to the next farm, in the next state. Many times, when green cards expire, they disappear into the Hispanic community as illegals, and take on other various labor jobs.

As migrants often suffer from diabetes, they need expert education and care. The family suffering from complications from diabetes is great. With loss of limbs, such as in Henrico’s case above, the family unit suffers along with the patient.

At some point, their lack of care will impact society by straining emergency systems and other services as these patients get sicker. Some clinicians in Minnesota and North Dakota came up with a concept that serves the migrant population with an innovative new style of service delivery.

Cluster clinics for Hispanic farmworkers

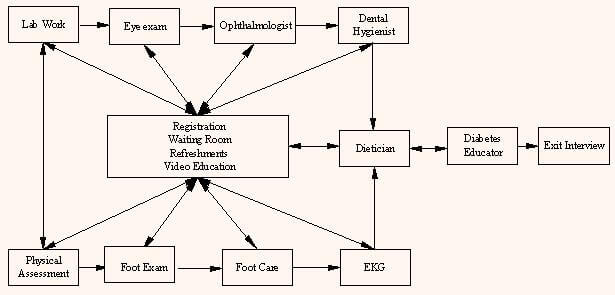

Frequent office visits, and multiple specialties and disciplines are required for quality diabetes care, and this new “go where they are” clinic approach seems to serve this purpose well. Clinicians came up with a popular concept that has been used to provide cluster clinics to serve these mobile populations all over the US. Each clinic is set up at a migrant camp, or in a setting near, or in a migrant community.

Barriers to farmworkers receiving healthcare

These are the many issues farmworkers face regarding healthcare.

Inability to pay, or no insurance

Inability to pay for health services is an issue, as the average farmworker makes a low wage. They also feel that they can’t miss work for doctor’s appointments. Work in the fields in strict, and from morning to sundown. Following work, they must shower before they go to classes or cluster clinic appointments, due to the pesticide residue that they may have on their skin.

Inability to take off work for healthcare appointments

We generally start our cluster clinics and diabetes education classes in the evenings, around 6 pm, and start the series after daylight savings time, when it is dark outside. The choice of day and time for the class is always important. It’s important to work with someone who knows what seasonally will be the best time for a class, before migrants move on to another state.

Other factors that present barriers to attending healthcare appointments

Participation seems to be good when we plan, provide transportation, a snack or meal for participants, child care, and it’s at a time slot that they can come for.

That sounds like many accommodations are made, and ones that we don’t provide for other populations. Most Americans do have to take off for medical appointments and diabetes classes. Farmworkers may not have fairness in the workplace like Americans do. They are denied many of the privileges that other workers in the US enjoy.

Cluster clinics provide a one-stop-shop for integrated diabetes care

Diabetes cluster clinics and diabetes education provides for a reduction in the mortality rate of farmworkers, and provides a stream-lined one-stop-shop for medical care and diabetes education. (2)

Culturally sensitive services

Services that are provided are culturally sensitive, and focus on self-management skills. Within each cluster clinic, there are an array of services in sub-clusters. We use outdoor tents, and partitions for privacy.

Our farmworker cluster clinic in North Carolina

We have a check-in point, and then they go to see the nurse for history and physical, including blood pressure, height, and weight. This is followed with a visit to the primary doctor, who recommends referrals. They are then sent to the podiatrist for foot examination, to meet with the diabetes educator, and to have a vision screening, hearing and dental evaluation. The clinic offers laboratory services with rapid A1C testing, all on the grounds of a farm barracks, or in a Hispanic community.

How other regions handle cluster clinics for migrant farmworkers

In other counties that are even more rural than our own, they have implemented the use of lay diabetes educators, teaching DEEP or the Stanford Diabetes Self-Management Program out in the community centers or churches. This just gets the message further out into the Hispanic community. Lately, there is more isolation due to political discourse, and fear of violence against minorities, or unlawful deportation related to the current administration.

Fear of discrimination, lawful or unlawful deportation

The higher the fears intensify with the new Nationalism, it’s more likely that Hispanic people with diabetes, whether farmworkers or not, may decide not to seek care for their diabetes. Fears of discrimination are great, as anger against immigrants grows with the political rhetoric in Washington.

Minnesota and North Dakota Cluster clinic study

Clinicians in Minnesota and North Dakota used a questionnaire, and interviews of Hispanic farmworker clients, given out at 37 different cluster clinics to study effectiveness and other factors. Most clients reported that multidisciplinary cluster clinics provided them with excellent or good diabetes care. 666 clients were surveyed and interviewed in the study. Subjective answers to open-ended questions helped the clinicians come up with the following conclusions:

- Clients perceived quality of care

- Clients benefitted from care that they found valuable, and might otherwise have not received due to lack of insurance, money for care, or access

- Clients saw the benefit of receiving all needed services in one visit, and found it convenient

- Services delivered were felt by clients to be culturally sensitive, and delivered in Spanish

- Clients received evidenced-based services

Conclusions of the cluster clinic study

The clinicians concluded that cluster clinics improve the quality of health services for an underserved population of Hispanic farmworkers. The clinics delivered single-setting services, that are accessible by farmworkers, and delivered in their native language. Participants received health services, education, and providers work together to provide a seamless service with effective communication. Outcomes for diabetes are improved, with improvements in A1C, and all related biomarkers.

Challenges to this kind of rural clinic in farm settings include:

- Difficulty with cooperation from farm owners

- Location of land or a facility to hold the clinic

- Recruitment of providers to staff rural clinics after working the day shift somewhere else

- Maintaining effective communication and follow-up throughout due to mobility of clients

- Funding issues

- Migrant fears of discrimination or unlawful deportation regardless if legal green card holders or not

- Collaborative efforts to get volunteer providers and support staff together at a remote location can be difficult

- Patient confidentiality can be an issue with multiple collaborating providers

- Trust can be an issue that affects participation, due to current feelings toward immigrants and fears of deportation

Where are cluster clinics held?

Often, cluster clinics may be held at a school, church, or government agency, if they are not held out at a farm or in the Hispanic neighborhood. Still, it seems most often these clinics are brought in, and put up as “tent cities” of sorts, for lack of a location, or for remote migrant camps. Providers must be in tune to culture, and must be always evaluating the literacy and understanding level of patients, to make sure that language and cultural barriers do not impede learning about their diabetes.

How are cluster clinics funded?

Migrant programs are grant funded by Rural Health Outreach, which have shifted to federal funds. For now, they are being supported, but as is the way with grant funding, monies could get cut. They are, in fact, in jeopardy every year. For the aspect of reducing health disparities in the migrant farmworker population, the model serves as an excellent service delivery method for this population where other service delivery methods fail. (3)

Community-Based Participatory Research project (CBPR)

Another community-based participatory research project was conducted within the Hispanic farmworker community. Called Formando, or “Shaping our Future,” the project focused on Type 2 Diabetes. It was designed by a group of university researchers, and community health workers in Southeast Idaho who worked with the Hispanic community.

It is a good example of health-focused advocacy with Hispanic agricultural migrants. Interviews conducted include 172 related to participant’s education level about Type 2 Diabetes. The interviews also included Hispanic women and their families. Several very significant and interesting insights into the Hispanic farmworker community have come from these interviews. As people in the Hispanic community age, Body Mass Index tends to increase, along with A1C.

What was more interesting was a tendency for the community to have a negative feeling about being thin. Thinness was equated with being vain, dieting with starvation, and developing diabetes with “structural violence” of the immigrant life.

“Structural violence,” refers to a social arrangement that puts someone, or someone within a population in the way of danger. Generally, structural violence is what happens to those who are not allowed to move forward in society, due to class systems or social constraints. (4)

Effect of “Promotoras” (Bilingual Community Health Assistants) on Migrant Farmworkers with diabetes

Yet another study of the Hispanic migrant farmworkers looked at a community on the Mexican border. They sought help of the “promotora,” or bilingual community health worker to foster trust and offer supports to affect self-management of Type 2 Diabetes.

The “promotoras” made hospital and home visits, provided telephone support for patients, and facilitated support groups. Data was collected on 70 participants at their doctor’s visits. They were given a pre-and post-questionnaire that asked about their perceived level of support, and how much they felt that it helped their self-management behaviors.

High risk participants had their A1C levels drop by 1%, with a reported sense of increased support from the “promotora,” and from family, friends, church, and community members.

Though most migrant farmworkers in the eastern United States were Hispanic or Latino in the 1990s, there are also non-Hispanic or Latino individuals that also migrate for farming jobs.

Diabetes education classes for Hispanic farmworkers

The diabetes educator may assess them on site at the cluster clinic, and then schedule them for a series of evening diabetes education classes. May times, when there is an acute issue, the diabetes educator and farmworker staff will make home visits. They may also schedule education sessions one-on-one, like the one I did recently at a local blueberry farm.

Teaching farmworkers diabetes education to Hispanic farmworkers

The farm I go to is no ordinary operation. It spans acres, and includes giant warehouses where blueberries are processed. I visit clients with the farmworker staff there, and come home with several quarts of blueberries for my time.

The warehouses stretch out, and it takes some time to walk through one. Though I don’t speak Spanish except for a few phrases or words here and there, often they do speak some English. The farmworker staff interpret spoken word, translate written word, and provide cultural directives to the educator, and this seems to work well for communication.

Transportation and child care is provided for clients

There is also a need for transportation. Grant programs often cover transportation to and from medical appointments and classes for farmworkers with diabetes when possible.

When we schedule our large diabetes education sessions in the evenings following daylight savings time, we provide transportation, and we have interns who take any children to another room for child care, to read books and play games with them while their parents are in class.

A full ethnic meal, or a healthy snack is always served for class

Sometimes, we serve a full ethnic meal. This works great to portion out what they should be eating on the right sized plate, and we serve them the right portions. Other times, we serve a healthy snack. The farmworkers prepare sautéed chicken, onions, and tomatoes, along with Spanish seasonings, and serve these in corn tortillas.

They fixe a delicious lime salad with next to zero carbohydrates. This consists of shredded lettuce, cucumber, tomato, and onion chopped fine, and a simple dressing of lime juice. We have a half cup of ice cream, or some fruit for a dessert.

A working dinner

They have a working dinner, where they learn how many tortillas, how much rice, and how much beans that they should put on their plate. They learn that corn tortillas are better due to corn being a whole grain. They learn that half of their plate should be greens, and how much avocado is a serving size.

Women are taught to get 3 servings of carbohydrates, and men are taught to eat 4 servings of carbohydrates, per the American Diabetes Association standards.

At the first farmworkers class, we served the lime salad on half the plate, a two thirds cup of brown rice, and grilled chicken with spices, onions and peppers.

Hispanic migrant community gathers around food

It would likely be inappropriate to omit the evening meal, or at least a healthy snack. The farmworkers coming in from the field may have not had time to eat, and therefore at least a snack is always provided.

A need to keep an entire class from bottoming out from a low blood sugar becomes paramount. Also, in Hispanic culture, food is an aspect of communal coming together for mutual benefit, and most gatherings in the farmworker community do include food.

The farmworker program will provide a glucometer through a special understanding with a local pharmacy. Medications for diabetes are most often paid for through rural health center grants, and provided through those primary care offices.

Lunch cooler for hot days in the field

For our class, we provided a “Diabetes MyPlate” in a lunch cooler for participants with diabetes to help create their plates, and carry with them out in the fields. We also provided a large water bottle, so they could stay hydrated on long, hot days in the sun.

Farmworkers are often victims of exposure not only to heat and elements, and hard labor with long hours, but also to being sprayed with pesticides in the fields. They are exposed to many chemicals, and it’s not certain as to how that would relate to the high incidence of Type 2 Diabetes, if at all.

There have been several cases of LADA (Latent Autoimmune Diabetes in Adults) in our farmworker population. I often wonder how much their exposure to chemical pesticides plays a role in the development of this autoimmune response. More studies should be done related to this.

One of our farmworker interns came up with a wonderful carbohydrate counting brochure, and we were able to teach participants to count carbohydrates. They learned to pick out serving size, and total carbohydrates on an English label. It worked very well, as they could start counting out the carbohydrates in the meal they were served.

It seemed that lightbulbs were going on all over the room, as they looked to their neighbors and smiled as they could obtain the skill with ease. They received 10 hours of DSME, divided up into initial assessment by the farmworker staff, 4 classes to include information on general diabetes, nutritional information, including hands on with portion sizing, label reading, and carbohydrate counting, with a cultural twist.

We used the Healthy Interactions flip charts for the first class, we then obtained a set of Spanish Conversation Maps. We gave each participant a copy of Herc Publishing’s “El Manego de la Diabetes,” or “Diabetes Management,” available from the publisher here: https://www.hercpublishing.com/products/detail?object=3561

Other recommended colorful, low literacy handouts in Spanish are available from the Texas Migrant Diabetes Council, or directly from their website. You can also order free diabetes information, or download handouts:

- https://www.dshs.texas.gov/diabetes/patient.shtm

- http://www.migrantclinician.org/toolsource/resource/texas-diabetes-council-diabetes-toolkit-providers.html

Reflections on migrant farmworker life in America

This was, in part, an article about my migrant farmworker class, and how appreciative and cooperative the people are. So humble, they take in every bit of information. They see that a provider who is willing to sit down and work with them for hours on their diabetes as a rare and precious thing, that they and their families cherish. I have never had a chance to work with a more engaged group of people.

That being said, this article is also in part an editorial piece about the state of migrant farm workers in America today.

As I ride down the interstate on I40, I see signs for a car dealership that says, “Thank a farmer three times a day.”

As you sit down tonight at your dinner table, after leaving your 9 to 5 job, where you can take off for your medical appointments, think about who also helped you get the produce on your table.

When you see the colorful bounty of harvest this fall spread out on your dining table, it was not just the farmer. It was these migrant farmworkers who live in such poverty among us making sure that you have fresh fruits and vegetables.

Further reading:

Over to you

What are your thoughts on this article about the state of farmworkers with diabetes in America today? Did you know that so many people living and working among us had so little access to healthcare? We would love to hear from you. Do you feel engaged to help farmworkers who help to put food on your table? You can donate to farmworker justice here: https://www.farmworkerjustice.org/support/make-donation

Following the recent hurricanes in Texas and Florida, many migrant farmworkers in these areas are displaced. You may donate to migrant farmworker hurricane Irma victims in Florida here: https://www.farmworkerjustice.org/support/make-donation

You may also donate to your local farmworker program for your county or region. Just google farmworker outreach programs in your area.

TheDiabetesCouncil Article | Reviewed by Dr. Jerry Ramos MD on June 01, 2020

References:

- http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0145721707304170

- https://search.proquest.com/openview/3cd4f5cb0e00ce9a4936aa499fe1728c/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=34124

- http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0145721707304170

- http://www.rrh.org.au/articles/subviewnew.asp?ArticleID=469

- http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1300/J013v43n04_06

- http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0145721707304170

- https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-0-387-88347-2_2